Expert Blog: May 35th 1989 - Tiananmen and the rise of memory activism

By Dr Tao Zhang | Published on 1 June 2024

Categories: Press office; Research; School of Arts and Humanities;

Expert Blog: May 35th 1989 - Tiananmen and the rise of memory activism

The Orwellian resonance of this non-existent date is slightly misleading. It does indeed relate to life in an autocratic state, but not directly to the diktats of a Ministry of Truth. China’s one-party state does of course, like Orwell’s Oceania, try to police thought, and to erase history. But this particular manipulation of the calendar is in fact a technique of resistance: a way of circumventing the taboo placed on all references to the bloody events of June 4th, 1989, in Tiananmen Square. Though Tiananmen has been effectively expunged from history textbooks in China, and though most of today’s Chinese young people are entirely ignorant of it, the endurance of the coded reference over many years is in itself evidence that history and memory are resistant to deletion.

During the now 35 years from May 35th, various form of ‘memory activism’ have stubbornly refused to let the shame and horror of a state turning its guns and tanks on its young citizens in a public square be forgotten.

A ‘memory activist’ has been defined as, ‘an agent (individual or group) who strategically commemorates the past in order to publicly address the dominant perception of it. Memory activists use memory as the crucial way of transforming society from below.’

One of the longest standing of these groups - the Tiananmen Mothers was formed as early as September 1989 by parents and friends of victims of the massacre and continues, doggedly, to seek truth and justice from the government and to publish details of those who died. Their persistence has received much coverage in the international media and has thus kept the issue alive in the global public consciousness.

Perhaps even more important has been the annual candle-lit mass vigil, in Victoria Park in Hong Kong, which lasted for 30 years from 1990 until its eventual suppression in 2020. The organization behind this - the Hong Kong Alliance - played a vital role sustaining memory activism until it was disbanded by the Beijing-imposed government in 2021 due to its ‘subversive stance’.

These forms of resistance are testament to the resilience of the democratic urge that inspired the student activists, and as such are a significant form of memorialization of the victims of the massacre. But it has to be admitted that the Chinese state has, if anything, become even more determined to suppress both history and democracy under its present leadership.

On May 28th of this year, six activists were arrested in Hong Kong for publishing "seditious" social media posts, ‘taking advantage of an upcoming sensitive day.’ For the most part, these posts were found to contain collections of ‘photographs and memories’ about the commemoration of the 1989 movement and the military crackdown. A double cancelling, then, of the original event and the evidence of its memorialisation.

A bleak picture is thus emerging of an increasingly dictatorial regime, convincingly captured in Standford political scientist Prof. Guoguang Wu’s notion of ‘the Stalinist Logic’ at play in Xi Jinping’s administration. This refers to the way in which the highly concentrated power structure, reminiscent of the era of Stalin and Mao, inevitably leads to spiralling leadership paranoia and ‘a Stalinist-style persecution and purge of cadres’. As he argues, in these circumstances, local authorities increasingly focus on answering to the central regime and toeing ‘correct’ policy lines by intensifying crackdowns on dissent.

For the present then, we can expect no great upsurge in popular resistance within China. However, in the wider world, there are signs, since 2020, of a new dynamism in the determination to keep the memory of Tiananmen alive, and of the emergence of a new generation of ‘memory activists’. And curiously the very increase in repression by Xi’s regime has been a main driver in this. We can identify two main factors in this dynamic.

Voice of America/Tang Huiyun

The Hong Kong exodus and the growth of globalised alliances

As of February 2024, over 600,000 Hong Kongers are estimated to have left Hong Kong following the introduction of the 2020 National Security Law. Most of these are professionals who have resettled in Europe, Canada, Australia, the US and Taiwan. In June, 2023, these newcomers were reported to have held vigils ‘at least 30 cities’ across the world.

But it is more than a matter of the expansion of an educated diaspora across the globe. Alliances between mainland Chinese, Hong Kongese, Tibetans and Uighurs have been growing and what may have been relatively isolated immigrant communities have come to constitute displaced communities of resistance to the regime in China. These groups took part in the memorial protests in London both on June 4th, 2023, and June 2nd 2024.

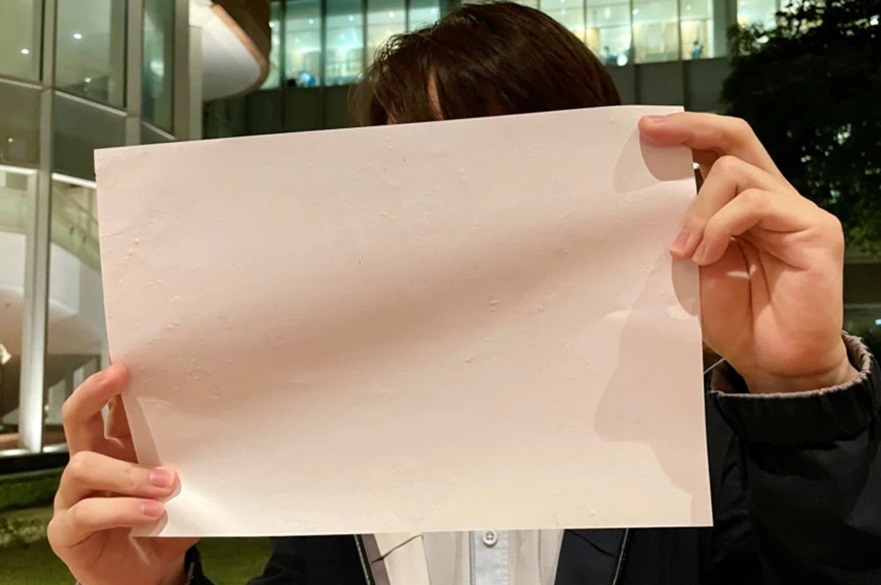

The A4 Movement’s embrace of June 4th

The A4 - or ‘White Paper’ movement – refers to an imaginative form of protest that emerged at the end of 2022 in response to the catastrophic Zero Covid policy imposed by the Chinese government. Holding up blank pieces of paper signified protest to the policy, while not actually committing the offence of naming it. At the same time, the blank sheets symbolised the silencing of dissent on a wider scale. Among these protesters, Chinese students studying abroad soon found themselves coming into contact with an older generation of expatriate protesters. This connection was founded in their shared criticism of the party state and common aspiration for liberty and democracy. They began to take part in protests together, particularly the memorial protests and vigils relating to 1989. On the June 4, 2023, a group of Chinese students in London named the ‘China Deviants’ spoke openly about their ‘White Paper’ identity and staged a rally in Trafalgar Square, displaying posters and photos of the massacre, alongside plastic tanks and other props. On 2 June, 2024, they staged a protest with other groups including one of the 1989 student leaders, Zhou Fengsuo. Beyond the UK, the ‘While Paper’ activists also organised and attended 1989 memorial events in many parts of the world including Paris, Tokyo, the US and Australia.

The Importance of Remembering June 4th

One of the 1989 student leaders, Wang Chaohua, stressed the vital importance of remembering June 4th in a recent interview with Podcast Bumingbai. Now a professor at UCLA, Wang views June 4th as a major turning point of the contemporary Chinese history. The Party state’s employment of lethal force to crush peaceful protesters and civilians established the absolute rule of the Party in the post 1989 era. This annihilation of nascent democratic aspirations opened the way to the distorted ideology of the Party’s ‘economic performance legitimacy’, which has informed the global rise of a neo-totalitarian China. Wang argues that to remember June 4th is to preserve collective memories of counter-state narratives and kindle the spirit of morality, justice and conscience displayed in the 1989 movement. This, she argues, is crucial for the future of the country, since without these moral foundations, economic growth will only lead China further down the path of lies and deceit.

As we witness the global dangers of China’s support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, its policy of clandestine interference in democracies, and its increasingly belligerent stance towards Taiwan, we could add that remembering June 4th is also vital for the world.