Expert Blog: Baldwin anniversaries

An expert blog on James Baldwin by Distinguished Professor Sharon Monteith

Published on 12 August 2024

Categories: Press office; Research; School of Arts and Humanities;

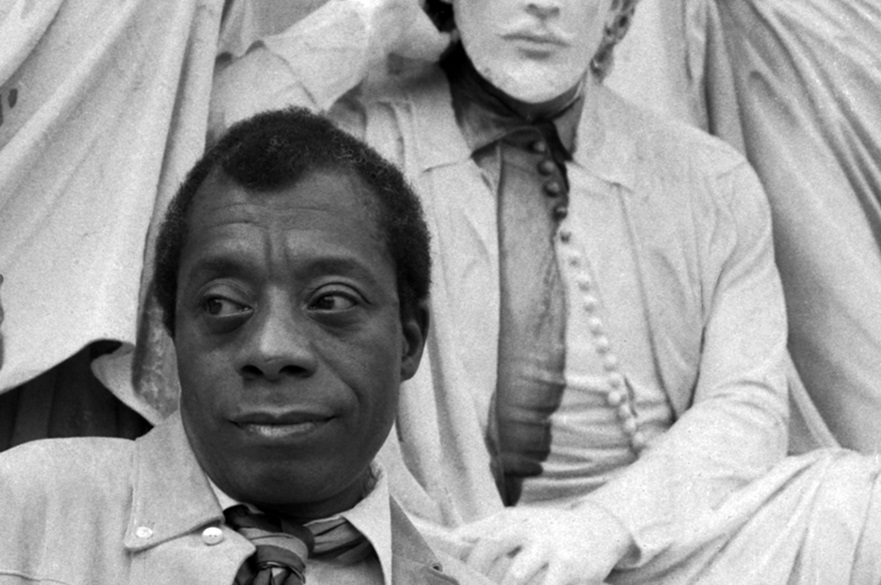

The recent anniversary of James Baldwin’s birth on August 2, 1924 commemorated the activist writer whose incisive diagnosis of racism and racial terrorism, whiteness and white supremacy resonates in this moment.

Baldwin was an artist who celebrated the artistry of others who asserted the importance of creating social and personal change. He described blues singer Billie Holiday as his poet: “She gave you back your experience. She refined it, and you recognized it for the first time because she was in and out of it and she made it possible for you to bear it. And if you could bear it, then you could begin to change it. That’s what a poet does.” It is what Baldwin did across six novels and many, many, more essays, as well as plays and occasional poetry.

When interviewed by The Black Scholar in 1973, and asked to comment on how the civil rights movement had changed since he began writing about it in 1955, Baldwin dated his involvement in the movement to his birth in 1924, by which time, he said, it was already all too clear that “the so-called standards of white civilization” were spurious and constituted no way to live. In 1924, William Pickens, an activist educator and member of the oldest civil rights organisation still in existence in the US, the NAACP, depicted the struggle for civil rights as “the fight of all the ages.” His poem to that effect was published in a socialist Black magazine, The Messenger, and Baldwin would throw himself into the same long fight, publishing across all the major activist publications over his writing career.

Battling against white supremacy and for civil rights was dangerous. Everything Baldwin published and everything he said in newspapers and during television interviews and debates was considered inflammatory by the FBI. J. Edgar Hoover’s organisation put the writer under surveillance from 1960, the year in which Baldwin made an open commitment to the movement, telling the civil rights groups SNCC and CORE that he would never betray them or their ideals. When the FBI closed Baldwin’s file in 1973, it totalled 1,884 pages.

CORE’s David Dennis who often introduced Baldwin on his speaking tours in the 1960s, witnessed the writer listening closely to civil rights organizers while making notes, “the proverbial fly on the wall, constantly thinking and breathing in the movement.” As one admiring writer friend observed of Baldwin, he knew “when to push the typewriter aside and march through the streets.” While drafting Blues for Mister Charlie— which premiered sixty years ago in 1964— Baldwin asked Dennis and another CORE organizer, Jerome Smith, to read parts from the play to test if the lines sounded natural to them.

On his sixtieth birthday in 1984, SNCC’s Julius Lester described Baldwin as a maverick for his refusal to bend to fashion or ideology and for sustaining his powerful social critique—and Baldwin told Lester, “No society can smash the social contract and be exempt from the consequences, and the consequences are chaos for everybody in the society.” He confessed that his testimonial activism as a moral witness to racial terrorism exhausted him but that it was a responsibility, an obligation, a passion. African American journalist Hollie West crystallized Baldwin as “the avenging prophet of American letters” who warned of Armageddon in the 1960s and was foretelling gloom in the 1980s. Like Lester, West observed Baldwin’s battle fatigue, though, because while a great deal had changed on the surface, he feared that “nothing has changed in the depths.”

Since Eric Garner pushed out the words “I can’t breathe” eleven times before passing out surrounded by police and EMTs, none of whom attempted to revive him on July 17, 2014, the police chokehold swelled the movement for Black Lives into the most forceful ethical stand and societal critique. With the world watching, Baldwin’s words would appear on placards at Black Lives Matter demonstrations, begin feeds on Black Twitter, and remain focal in defining the active communitas that would transform all our societies into ones in which Black, Asian and Hispanic lives have equal value with white lives. Baldwin had long-range vision and searing insight. In 2016, his legacy was threaded through The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race, a powerfully emotive essay collection for which Mississippi writer Jesmyn Ward riffed on the tilte of Baldwin’s 1963 testament The Fire Next Time.

In Britain, Manchester University Press has been publishing The James Baldwin Review since 2015, analysing Baldwin’s writing and promoting his activism. Just a few days ago, the annual Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha conference was held at the University of Mississippi in Faulkner’s home town of Oxford. Baldwin featured heavily in our panel on civil rights because his essay “Faulkner and Desegregation” (1956) encapsulated the depths of intransigence against enacting civil rights legislation in the 1950s. Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha is the longest running conference devoted to a single writer. It is celebrated its fiftieth anniversary this year. Now is the time to have an annual celebration of Baldwin. It is long overdue. Let’s dedicate his birthday to sustained and in-depth discussion of Baldwin’s life, legacy and his relevance to activism on race and rights now.