Expert Blog: A history of succession to the throne

By Professor Martyn Bennett, a professor of early modern history

Published on 14 September 2022

Categories: Press office; Research; School of Arts and Humanities;

The succession of Charles III has been smooth, and it would, given that we are in a position where we seem to know line the succession for the foreseeable future, confidently expecting the next monarch to be William V and after that George VII seem inevitable. This has not historically been the case and at several times there have been crises in the line of succession that echoed around the country.

The most recent of these was in the 1930s when King Edward VIII stepped down after becoming king following the death of his father George V. King Edward chose to marry the love of his life, the divorcee Wallace Simpson rather than continue as king. Much has been made of how this unexpectedly thrust Elizabeth into the very forefront of the line of succession. This is perhaps overstated. Even if Edward had become king, with Wallace as queen consort, he was childless and as his brother died in 1952, at Edward’s death in 1972, Princess Elizabeth would have succeeded him then.

This has by no means been the greatest crisis and a look back at the last few hundred years shows.

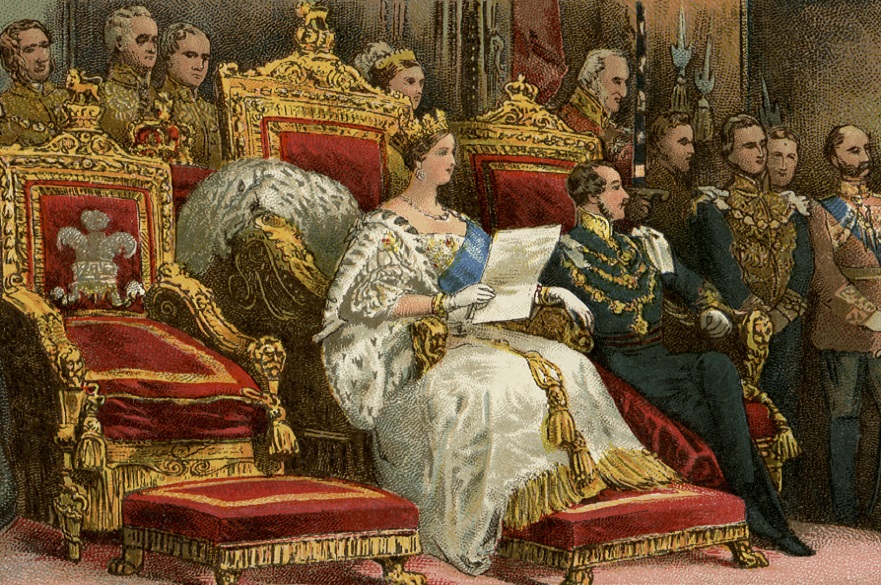

In the early nineteenth century the sons of George III had entered into a ‘race’ to produce an heir to catty on the House of Hanover line started in 1715 by George I. The outcome of this race was the birth of Queen Victoria who succeeded her uncle William IV in 1837. The Hanoverians themselves had only succeeded to the thrones of the three kingdoms following the death of last of the Stewarts, Queen Anne. Getting them there had a convoluted process line involving the descendants of Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia, the sister of Charles I. The result was a king who did not speak English on the throne.

The predecessors of the Hanoverians, Stuarts or Stewarts themselves had also come to the thrones through a less than direct manner. Whilst James VI of Scotland had the strongest claim to the thrones of England and Ireland, there were others, and the issue was surrounded by confusion caused by secrecy. Queen Elizabeth I had prohibited discussions about the succession and one MP was imprisoned for even asking if the issue could be discussed. James VI was descended from Henry VII of England’s sister. He was of course son of Mary Queen of Scots, whom Elizabeth I had (reluctantly) had executed whilst James was a young man. Many were concerned about James’s succession for several reasons, including his mother’s reputation. For that reason, his rights to succeed were confirmed by the first Accession Council of the sort that met to proclaim Charles III on 10 September 2022. In the end it proved unnecessary, and the succession was smooth.

Elizabeth I’s own succession was the product of a confusing period following the death of King Henry VIII. He had three children, two girls and a boy. It was his youngest child, Edward VI who reigned first. He died whilst still a child and was officially followed by Queen Mary who overturned her father and brother’s Protestant Reformation. Fears that she would do so had in part resulted in a brief coup d’état which saw sixteen-year-old Lady Jane Grey of Groby. She lasted just nine days on the throne and was later executed by order of Mary I. The succession of Henry VIII was a smooth affair, but like Charles I he had originally been the second son and became heir after the death of his older brother Prince Arthur. Henry’s father King Henry VII had come to the throne by right of conquest, after he had of course defeated King Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

The fifteenth century had seen the succession issue reach its most complicated. The century had begun with King Henry IV on the throne, followed by Henry V and then the child king, Henry VI. Conflict over the direction of the young king’s rule resulted in the Wars of the Roses. The young king Henry was deposed and succeeded by Edward IV. Henry VI was briefly restored to the throne, only to be defeated on the battlefield and deposed again by Edward IV before probably being murdered. The sons of Edward IV disappeared in mysterious circumstances, becoming known as the Princes in the Tower. Their probable murders paved the way for Richard III.

Whilst the succession of Charles III was smooth and orderly it remains remarkable. The history of the monarchies within the British Isles have not always been so. Violence, deceit and tragedy have tended until very recent years to dominate succession to the throne. Even before the Wars of the Roses things had not always been smooth, with the Norman Conquest in the Eleventh Century, the murder of King William II; rival claimants in the twelfth century, and murders in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries marking the succession to the English throne. We should all be very pleased that recent events have been conflict free, unlike so much of our turbulent history.

Professor Martyn Bennett is a professor of early modern history in the School of Arts and Humanities