Expert blog: The King’s Revolutionary Guards

By Professor Martyn Bennett, a professor of Early Modern History

Published on 9 May 2023

Categories: Press office; Research;

The regiments of horse and one of the foot guards regiment which were guarding the new king on 6 May 2023 have surprising origins for regiments so closely associated with the monarchy. They are all the products of a military revolution in seventeenth century Britain and Ireland and are also inextricably bound up with the republican experiment which followed the civil wars (1639-1653).

Major changes in cavalry tactics and equipment: fully armoured cavalry, wearing a closed helmet and three-quarter armour and high-top leather boots was expensive. By the end of the sixteenth century many armies were beginning to dispense with them. The alternative was not particularly popular. More lightly armoured cavalry, cheaper to raise and support known as harquebusiers or arquebusiers were looked down on by commanders and armoured cavalry and often seen as dragoons rather than cavalry at all. Harquebusiers were named after their chief weapon a matchlock musket which was long, heavy and hard to fire from horseback. As a result it was probable that such troopers would use their weapons whilst dismounted. In the years before the civil wars in Britain and Ireland improvements were made in the harquebusier’s weaponry. Lighter, flintlock carbines replaced the harquebus. Steadily, the harquebusier became standardised. They wore four pieces of armour, a back and front plate, a barred helmet and an armoured gauntlet on their left rein holding arm. Under the body armour was a thick leather buff-coat. A fully equipped harquebusier would be armed with a heavy sword, two pistols carried in holsters on the saddle and a carbine. In the early days of the civil war this armour and equipment would, for many troopers, be aspiration.

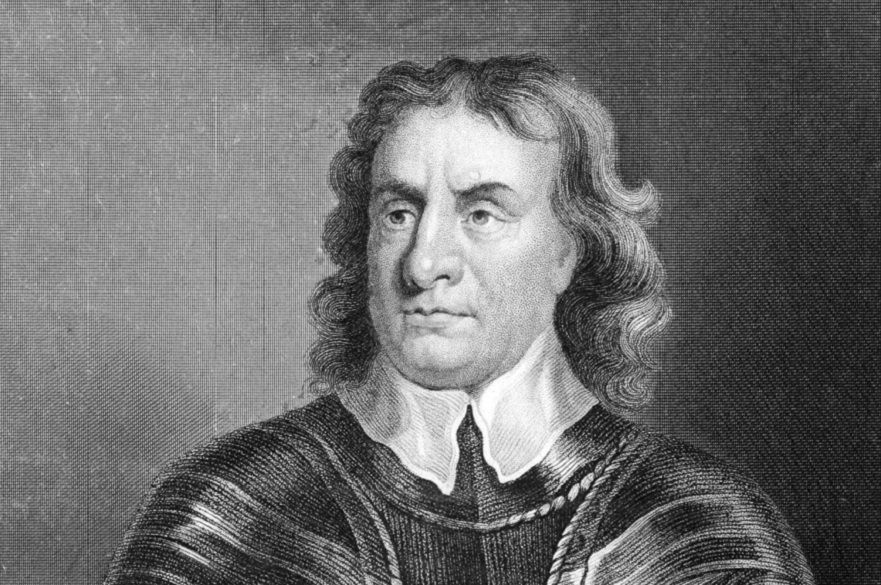

Use of cavalry on the battlefield had also developed in the first four decades of the century. The tactics of the fully armoured cavalry had been abandoned early on, but for some time cavalry troopers relied on their firearms before coming into contact with opponents. As the effective range of pistols was limited opposing regiments would advance to close range and discharge their firearms before ‘charging’. Therefore, contact was at quite a low velocity. However as the war in continental Europe, which would last some thirty years from 1618, progressed, there was a further shift in battlefield tactics. Instead some commanders favoured abandoning use of the pistols and instead begin to approach the enemy cavalry at a trot followed by a canter, gallop and finally a high-speed charge, relying on discipline to keep the soldiers close together and breaking the opposition cavalry with a combination of weight and velocity. This tactic worked best when the opposition was disordered, of poor discipline or using the outmoded tactic of relying on firepower. During the civil wars in Britain and Ireland a variety of tactics were used by cavalry commanders in the early days. The king’s nephew, royalist general Prince Rupert used the headlong charge from the outset catching the enemy off balance at the Battle of Edgehill. Within months parliamentarian colonel, Oliver Cromwell was emulating the prince in small skirmishes in East Anglia. As Cromwell rose to the rank of lieutenant general he was able to lead more and more cavalrymen in dramatic charges at the battles of Winceby, Marston Moor, Newbury and Naseby. Cromwell and his colleagues honed the cavalry charge to perfection, making parliamentarian cavalry feared and respected at home and abroad. Through these developments the harquebusier became the standard medium/heavy cavalry in the civil wars.

The cavalry regiments which now comprise the Household Cavalry began their lives as harquebusiers and thus were part of two revolutions – the civil wars in Britain and Ireland and the military revolution which affected warfare throughout Europe in the early modern period. One from Cromwell’s own regiment. Cromwell had several cavalry regiments. The first was based on the single troop of horse parliament authorised him to raise in the summer of 1642 which grew to become a double-sized regiment within a year. In 1645 when the New Model Army was created and Cromwell, because he was an MP, was temporarily barred from commanding forces in the field, was divided into two separate regiments, one became the Lord General Sir Thomas Fairfax’s regiment and the other was led by Colonel Edward Whalley. By 1646 Cromwell, by now lieutenant general of the New Model Army, had a new regiment and so this continued until his death in 1658 when it passed first to his son Richard, the second Lord Protector before passing into the hands of Colonel Edmund Ludlow. It may be that the regiment which served the Lord General at home also incorporated a troops raised on Cromwell’s orders in 1650 in the northeast as the war with Scotland loomed because Cromwell’s second regiment remained in Ireland during the decade after Cromwell's departure in 1650. The new unit became the Royal Horse Guards (the Blues) following the Restoration. The second cavalry regiment which survived into the restoration belonged to Colonel George Monck a military theorist and a general in the 1650s. Monck was Cromwell’s deputy in Scotland after his impressive string of victories in 1651, which had brought the war in Scotland to an end. Part of his regiment of horse was incorporated into the Life Guards after the Restoration of the monarchy joining three troops of horse raised by the future Charles II in the United Provinces (Holland). Because of its being founded by Prince Charles, this regiment was given seniority over the older regiment created on Cromwell’s orders. Nevertheless these two regiments which had grown out of the revolution Monck’s infantry regiment was incorporated into Charles II’s standing army as the Coldstream Guards. By the late eighteenth century the Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards had given up wearing back and breastplates. Ironically, it was contact with contemporary harquebusiers once more an outcome of a revolution: Napoleon’s cuirassiers at the Battle of Waterloo (1815), which inspired the readoption of the body armour which was highly polished for 6 May.

Professor Martyn Bennett is a professor of Early Modern History in the School of Arts and Humanities