OPINION: Gareth Thomas- Living Proof

Connor Murphy provides his thoughts and insight into Gareth Thomas announcing his status as HIV positive.

By Connor Murphy | Published on 18 September 2019

Categories: Press office; School of Arts and Humanities;

On 14th September 2019, rugby star Gareth Thomas announced his status as HIV positive. This was not, however, a willing proclamation; Thomas was being blackmailed by, as he described, ‘evils’: ‘Even though I have been forced to tell you this,’ he said, ‘I choose to fight, to educate and break the stigma.’ While it is absolutely commendable to announce this on his own terms, we must address the societal conditions that enable the blackmail of a prolific member of the LGBTQIA+ community. Headlines read ‘Gareth Thomas: Ex-Rugby Captain has HIV’, perpetuating the focus on his private life rather than on the blackmail that made it public. Of course, this is nothing new: the lives of people who go against the grain of heteronormativity — the culturally-propagated ideal of a union between man and woman — have been under perverse scrutiny for quite some time.

HIV prevention and treatment strategies have come a long way since the ‘80s — also known as the ‘era of gay panic’, in which over 22,000 people died from complications to the disease in this singular decade. With the introduction of PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis), PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), and developments in antiretroviral therapy, there is a momentous wave of optimism surrounding this disease: we can prevent it, and we can treat it. From a scientific perspective, it is no longer the ‘death sentence’ that it was just thirty years ago (Park, 2016).

Those who are diagnosed can go on to live healthy lives, and, with effective treatment, can become unable to pass HIV on to others (Undetectable = Untransmittable). These are, undoubtedly, reasons to rejoice — so, what for what reason does this diagnosis become leverage?

‘The appearance of [HIV and] AIDS among gay men’, writes Monica Pearl, ‘was not the first time that homosexuality in men has been associated with loss, mourning, and death.' Before the AIDS Crisis, being gay represented different kinds of death: of the nuclear family; of parental success; of social obedience and acceptability; of hetero-masculinity. With the onset of the crisis, these symbolic deaths took corporeal form, a very physical manifestation that appeared to make the irrationality of homophobia rational, as if even our bodies reject same-sex desire.

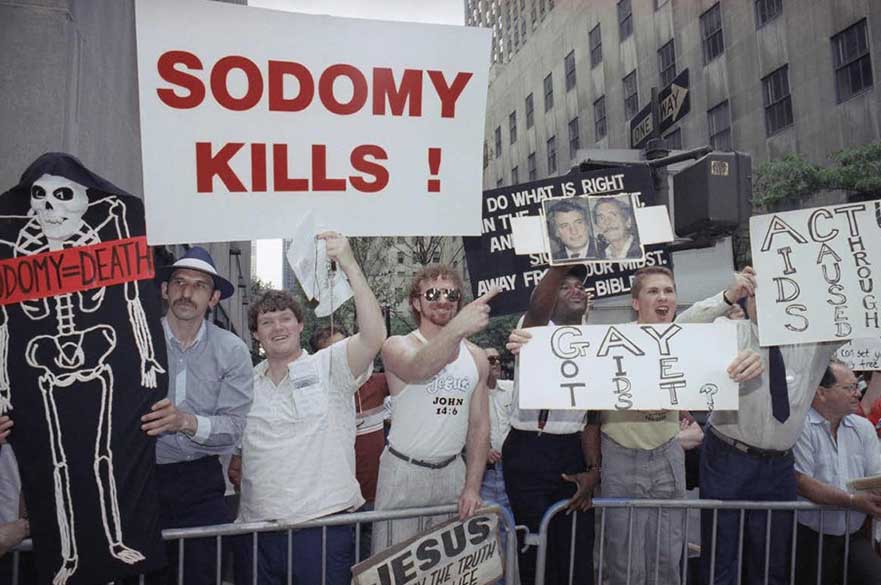

Credit: David A. Cantor

Look at this photograph

Note the smiles on these faces: gleeful expressions as if to say, ‘I told you so.’ This is a photograph of anti-gay protesters circa 1990, in which the words ‘Sodomy Kills’ act as a blunt encapsulation of this perceived gay/death relationship. Even though our society, and its perception of homosexuality, has taken great strides over the last thirty years, homophobia takes quieter and more insidious shapes, such as a blackmail that has the potential to destroy public credibility. The forcing of Thomas’s hand, regarding his diagnosis, is confirmation of the continued subjugation of homosexuality as a cultural category — that it can still be weaponised in ways that should, in this century, be unthinkable.

On 15th September — the day after his Twitter announcement — Thomas went on to complete the Tenby Ironman, a gruelling mega-triathlon that most men could only dream of achieving. As Thomas crossed the finish line, he broke into tears and embraced his husband. There is a certain heroic irony here: no disease, no sexuality, no blackmail that is bolstered by a homophobic cultural past, can obstruct a man who is destined to succeed, regardless.

Notes for Editors

Press enquiries please contact Emily Oakden, communications executive, on telephone +44 (0)115 848 5376, or via email, or Chris Birkle, public relations manager, on telephone +44 (0)115 848 2310, or via email.

About Nottingham Trent University

Nottingham Trent University (NTU) was named University of the Year 2019 in the Guardian University Awards. The award was based on performance and improvement in the Guardian University Guide, retention of students from low-participation areas and attainment of BME students. NTU was also the Times Higher Education University of the Year 2017, and The Times and Sunday Times Modern University of the Year 2018. These awards recognise NTU for its high levels of student satisfaction, its quality of teaching, its engagement with employers, and its overall student experience. The university has been rated Gold in the Government’s Teaching Excellence Framework – the highest ranking available.

It is one of the largest UK universities. With nearly 32,000 students and more than 4,000 staff located across four campuses, the University contributes £900m to the UK economy every year. With an international student population of more than 3,000 from around 100 countries, the University prides itself on its global outlook. The university is passionate about creating opportunities and its extensive outreach programme is designed to enable NTU to be a vehicle for social mobility. NTU is among the UK’s top five recruiters of students from disadvantaged backgrounds. A total of 82% of its graduates go on to graduate entry employment or graduate entry education or training within six months of leaving. Student satisfaction is high: NTU achieved an 87% satisfaction score in the 2019 National Student Survey.

NTU is also one of the UK’s most environmentally friendly universities, containing some of the sector’s most inspiring and efficient award-winning buildings.

NTU is home to world-class research, and won The Queen’s Anniversary Prize in 2015 – the highest national honour for a UK university. It recognised the University’s pioneering projects to improve weapons and explosives detection in luggage; enable safer production of powdered infant formula; and combat food fraud.