Expert Blog: Remaking the region - the East Midlands in transition

Professor William Rossiter, Nottingham Business School, explores the nature and development of the East Midlands region and considers the wider implications for devolution in England.

By Professor William Rossiter | Published on 16 May 2025

Categories: Press office; Research; Nottingham Business School;

It is one year since the creation of the new East Midlands County Combined Authority and the election of our first mayor Claire Ward. In this respect, the region has entered an interesting, indeed exciting, phase of institution building. Over the course of this year the Labour Government has also published a Devolution White Paper mapping out plans for the extension of devolution to all parts of England not currently covered by devolved institutions while also heralding a wholesale reorganisation of local government on the unitary model. Whether the Government has the bandwidth to manage both processes simultaneously remains to be seen. The arrival of Reform as a force in local government in the region after May’s local elections, winning control of both Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire County Councils and the newly created mayoralty in Lincolnshire, may further challenge prospects for an orderly transition to new regional and local governance structures.

The prospect of such fundamental change to regional and local institutions makes this an interesting time to reflect on the nature of the East Midlands region and the lessons we may draw from its economic and institutional evolutions which, I would argue, have wider relevance to the implementation of future devolution initiatives in England.

Economic geographers have long understood that regions are not static. They are constantly being made, remade and reimagined, responding to internal dynamics and external influences. We see evidence of these reimaginings in the ways in which the East Midlands has been described over the years. Historical perspectives are instructive. Rowlands (1987) described the region as “an area of debatable land frequently subject to competing powers”. This was a reference to the conflict between English and Danes in the 10th century, but it usefully frames the region as a contested and evolving concept. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the often-expressed view that the East Midlands lacks a strong sense of regional identity (Hardill, 2006), Dury (1963) saw the region as “the ‘portion’ of Britain left over when other, more recognisable, regions – Yorkshire, Wales, South-East England and so on – were filled in.”

In contrast, the noted historian W.G. Hoskins (1949) described the East Midlands as “the most unknown and neglected part of England” extending, in his view, from the Chilterns to the Trent. Later historians (Townsend, 2006) and industrial archaeologists (Smith 1965) have noted the importance the region’s traditional textile industries, such as framework knitting, in shaping the spatial distribution of economic activity and urban hierarchy in the region today. This view highlights the essentially polycentric character of the East Midlands in which the position of the medieval county towns became consolidated at the apex of the urban hierarchy as industrialisation and urbanisation took hold. This polycentricism stands in marked contrast to more traditional industrial regions such as those centred on the all-subsuming conurbations of Birmingham and Manchester. These two large (monocentric) city regions have been central to the emergence and propagation of the model of devolution articulated in the Devolution White Paper. And yet, in many ways, the polycentric character and political complexity of the East Midlands, as a mix two tier and unitary local government, is far more typical of the kinds of areas to which devolution is now being extended. What then can we learn from the evolutions of the East Midlands that is relevant to wider devolution in England?

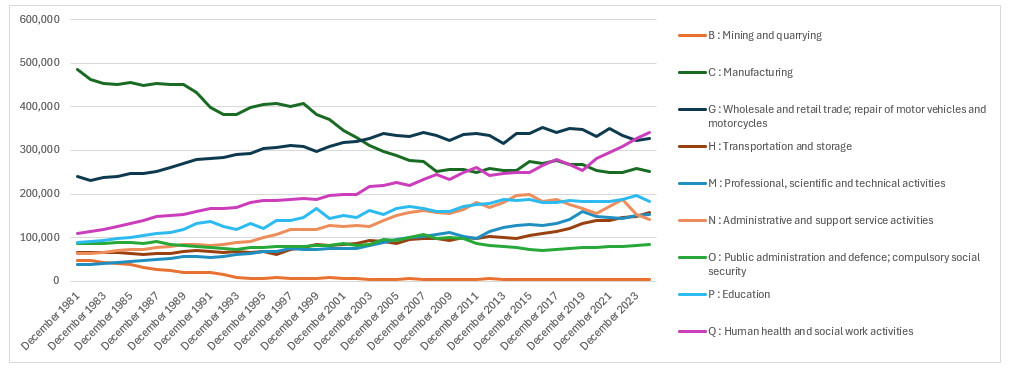

The present social and economic condition of the East Midlands cannot be understood without reference to the long-term story of structural change to which the region, in common with many other parts of the North and Midlands, has been subject. A region that was once based on manufacturing (and extractive industries) has substantially deindustrialised. Employment contraction in these traditional industry sectors has been offset by the growth of service sectors such as health, education and business services which are particularly strong in places like Nottingham:

Source: Employee jobs by industry (SIC 2007) - seasonally adjusted. ONS Crown Copyright Reserved [from Nomis on 14 April 2025]

This long-term structural change matters because it has had direct consequences for the economic opportunities accessible to the region’s residents and the socio-economic outcomes with which these are associated. Lower than average earnings and some of the lowest levels of Gross Disposable Household Incomes per head anywhere in the UK (ONS 2024) demonstrate the seriousness of the problem. In essence, this is the case for a strategy based on inclusive growth i.e. a model of regional development capable of delivering better socio-economic outcomes. The Mayor’s Inclusive Growth Commission is therefore an extremely welcome development for the region.

What can we do to shift the region’s trajectory of development in a more positive direction consistent with the objectives of inclusive growth? This is where perspectives from evolutionary economic geography can help to identify the scope for policy and local action to make a difference. Four key concepts capture the essence of this perspective on regional development:

- Path dependency – the idea that history matters. It doesn’t determine future development trajectories, but it does constrain them. We start from where we start, with a given set of historic capabilities or endowments that represent the raw materials at our disposal. The emergence of the biotech cluster in Nottingham is a great local example.

- Avoiding lock-in – the problem of becoming tied to time-limited sectoral or technological pathways. The role that coal played in North Nottinghamshire and that textiles played in Leicester could be seen as illustrations.

- Developing adaptive capability – the ability to weather economic shocks from any source and take advantage of new and emerging market opportunities, wherever they arise.

- Institutional thickness – a key determinant of adaptive capability. Recent regional policy history in the UK has shown that it is far easier to disrupt and dismantle local and regional development institutions than it is to reinforce and reconstruct them.

Institution building takes time, but it is essential if we are to chart our way towards a positive post-industrial future in the regions like the East Midlands. And that brings us back to our present exciting, but slightly uncertain, phase of institution building. What exactly will a successful development strategy look like?

For me, a good regional development strategy will seek to realise the potential of the polycentric region and seek to capitalise on the benefits of agglomeration without being hampered by the downsides. This will require a degree of spatial imagination in a structurally diverse and polycentric region. We will need a growth and opportunities plan based on the exploitation of place-based synergies. An economically and socially diverse region will not need the same interventions everywhere. The key measure of inclusive growth success will be the delivery of quality jobs at scale that are accessible to local people. In the process, I hope that we can build a collective understanding of our region and a shared regional narrative that speaks to the many and varied identities of the East Midlands and its people.

*This blog is based on Professor Rossiter’s Inaugural Lecture “The making, unmaking and remaking of an English Region: Unexpected journeys in regional development”, delivered at NTU in Nottingham on 29 April 2025.